Most boxers will tell you the punches don't hurt as much as the blows they take outside the ring.

Frequently being forced to take fights at the last minute, rarely being paid what you were promised and then finding your manager was working for the opponent. Those are the kind of setbacks that might fuel the anger, rage and bitterness known by many in the sport.

So, imagine being Len Johnson, a retired middleweight boxer with more than 100 fights behind him, entering Manchester's Old Abbey Taphouse pub after a tough day driving buses around town on a September night in 1953.

Johnson, then in his early 50s, was teetotal but he was ordering a round for his friends. Whatever optimism, banter and conversation the group had brought to the establishment was swiftly brought to a close in one moment. He was refused service and thrown out because of the colour of his skin.

It wasn't the first time the boxer had been discriminated against for being black. But Johnson fought back, just as he had done his whole career.

The British Boxing Board of Control's 'rule 24' stated that both contestants for one of their titles needed to have been "born of white parents".

The rule, given government backing when introduced in 1911, remained in effect until 1948. That same year, Dick Turpin became Britain's first black boxing champion, beating Vince Hawkins on points in front of 40,000 people at Villa Park. Turpin's brother Randolphwould in 1951 become world middleweight champion, defeating Sugar Ray Robinson.

Johnson wasn't the only successful fighter who found himself locked out of the sport's elite during that time. About 30 miles up the road in Liverpool there was a Guyanese boxer named Ritchie 'Kid' Tanner who was considered as good a featherweight as any, but never fought for the biggest prize.

The lack of acceptance for black boxers wasn't only a British issue either. At the start of the 1900s, the United States had responded with anger at the notion that the best heavyweight was a black man.

Jack Johnson - no relation to Len - endured such hostility during the seven years he carried the title of world champion from 1908 that he was eventually forced to flee his country because of a racially motivated conviction. He was pardoned in 2018, 72 years after his death.

Len Johnson was also forced into an escape. In 1926 he left Britain and spent six months in Australia, beating Harry Collins to win the Empire middleweight title (it would now be considered the Commonwealth title).

Johnson said the experience did him "the power of good", although a triumphant return to Britain did not follow. He was informed his title win wasn't recognised in his homeland. It was one of the many factors that led to his disillusionment with the boxing world.

"I'm barred from the Albert Hall and the national sporting club. In fact, whenever there is big money I'm kept out of it," Johnson said in 1930, as quoted in Michael Herbert's book about him, Never Counted Out.

"The prejudice against colour has prevented me from getting a championship fight. I feel now that there is no use whatever going on with the business."

Johnson's professional career was drawing to a close. His final fight came in 1933.

His affinity with the sport continued until the outbreak of World War Two, and he would still occasionally fight in the booths at travelling fairs.

But now the second act of his life was starting. One with a political punch.

Towards the end of the war, Johnson had joined the Communist Party. He was active in the community in Moss Side, Manchester, and frequently intervened in cases involving racial discrimination.

He had also been one of the local representatives at the influential Pan-African Congress of 1945, hosted in his home city.

During his boxing career, Johnson was very much considered a "local hero" in his community, as author Herbert explains.

"They'd all stay up when he had his big fights at Belle Vue," he says. "They'd wait until his taxi brought him home and there'd be a big cheer.

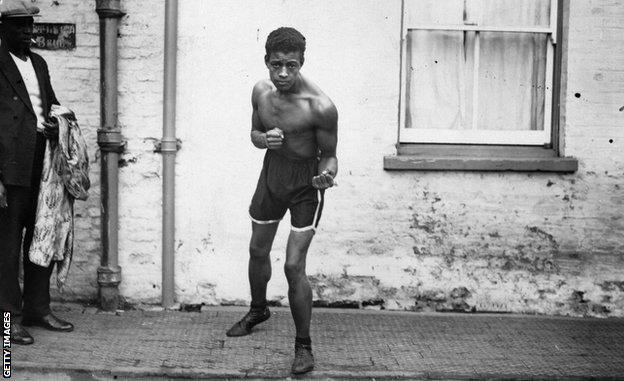

The eldest of four siblings, Johnson was born on 22 October 1902 in Clayton, Manchester to a father from Sierra Leone and a mother from Ireland.

His introduction to boxing came after he got into a fight at work and his dad, Billy, took him to watch a local bout. Johnson didn't immediately take to the sport, and it was to his surprise that his father signed him up to fight a couple of weeks later.

He had little knowledge of how to box, let alone how to prepare, but he trained as best he could. His mother provided an old clothes line which he skipped with.

The contest took place in 1921, at the Alhambra Theatre in Openshaw, Manchester. His opponent was fellow local teenager Jerry Hogan.

The inexperienced Johnson came out on top, with a third-round knockout, but it turned out there was a bit of luck involved.

"Jerry shoved his chin on to my hand and down he went for the count. I really had no idea how I knocked him out!" Johnson is quoted as saying in my Boxing's Uncrowned Champion, Rob Howard's book about him.

That first unlikely victory - lucky or not - was just the beginning.

No comments:

Post a Comment

We love to hear from you!

THANKS.